Stand-up Comedy. Proofs. Replication.

Politician A says, “Your policies have left millions without healthcare and basic medications. Will your party take responsibility?”

Politician B retorts, “Oh yeah? What about your party, which sent 80,000 of our soldiers to a pointless war, not to mention your cousin’s insurance scam that skyrocketed premiums and bumped up homelessness by 1.2%?”

Then, a stand-up comedian jumps in: “Gentlemen, gentlemen, let’s put this into perspective. It’s like being on trial for arson and your defense being, “But your honor, my neighbor runs an illegal underground casino. Can we focus on that instead?” Sure, it doesn’t make your neighbor a saint, but you are one who is being deposed at the moment! Spoiler alert: both of you are getting grounded by democracy.”

Funnily, the comedian’s frivolous argument makes more sense and sounds more logical than that of the dignitaries, but do we realize why?

Let’s dive into it.

* * *

There are quite a few methods of proving theorems in mathematics, for example proof by construction, proof by induction etc. One of the effective ones is called proof by contradiction, exemplified by the proof from middle school, that square root of two is an irrational number. The modus operandi:

- Assume the opposite of what you are trying to prove.

- From this assumption, deduce something that is obviously false or contradictory.

- Conclude that the original assumption must be false because it leads to a contradictory outcome.

A closely related technique to the above mathematical principle, commonly used in philosophy, is reductio-ad-absurdum. Here you demonstrate how a particular line of reasoning derived from an assumption leads to absurdity. That’s the technique employed by comedians for “calling bullshit”, making them seem more rational than those they critique.

In a deterministic setting which involves logical statements, proof with contradiction works well, but does it work equally well under statistical settings too?

Let us examine.

* * *

We live in a world with no complete guarantees. We can only assert that a new protein shake works for most people most of the time, barring a few people who do not benefit much from it. But how do we go about making these decisions? We conduct statistical hypothesis tests. They work as follows:

- Assume a contradiction to be true (null hypothesis), like a balanced diet sufficing for muscle growth, negating the need for a new protein shake.

- A control group maintains a balanced diet, while a test group also receives the protein shake.

- After similar lifestyle adjustments, muscle growth is measured.

- The p-value, or “bullshit detection” statistic, is calculated. A high p-value suggests the results of improved muscle strength could simply be by chance, indicating potentially overstated claims. A low p-value suggests the opposite.

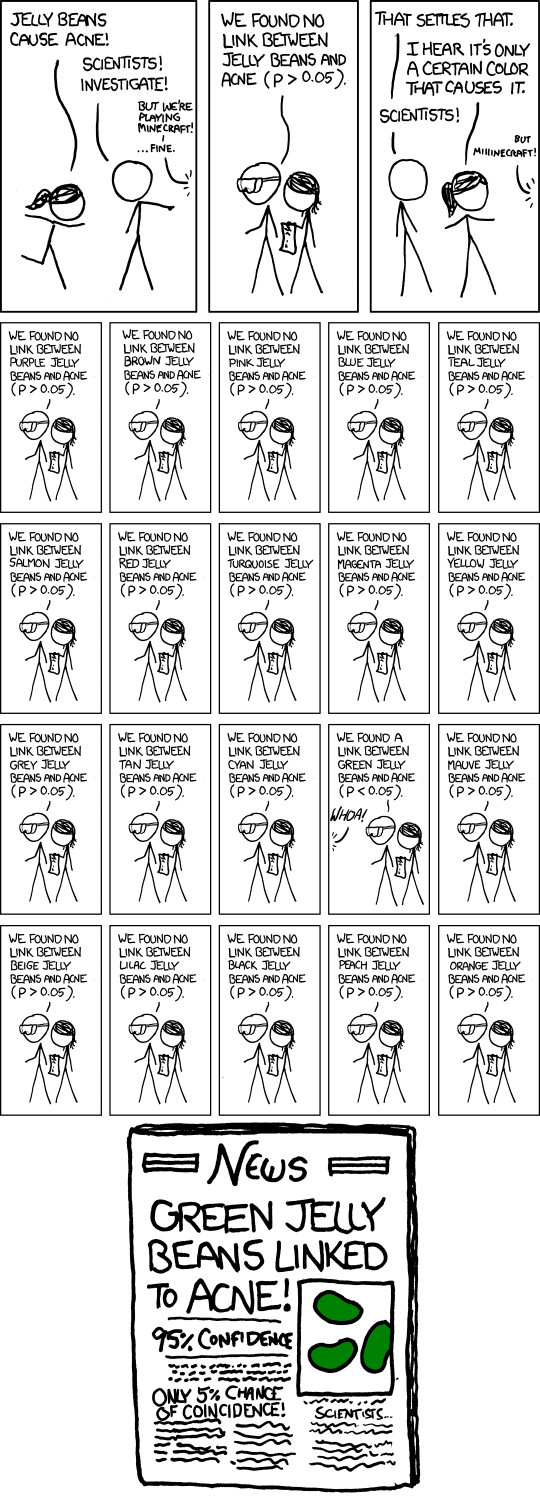

But here comes the catch! A statistical test involves choosing a threshold. The typical value for p is 0.05. This means, if contradictory evidence is less than 5%, it could suggest that the protein shake’s effect is statistically significant in having an effect on muscle growth.

However, consider the scenario where a pharmaceutical company conducts numerous tests to measure muscle growth using different compounds. Imagine rolling a twenty-sided die; statistically, one in every twenty throws will achieve the desired outcome by sheer chance. Similarly, in conducting twenty different hypothesis tests with a 5% significance threshold, one is likely to show a significant result, merely due to randomness. To mitigate this, rigorous methodologies such as replication tests, confidence interval judgments, and Bonferroni corrections have been developed. Yet every now and then, we hear about replication crisis crippling a scientific discipline. Why is that?

As a grad student, I used to chuckle at other fields of study having these replication crisis, but not sciences and technology shielded by picking low thresholds. (Higgs Boson experiment’s p-value was 1 in 3.5 million). Reality caught up with me personally, when I started working in big-tech companies where A/B tests are pivotal to their functioning. Picture a force of over 20,000+ technical minds, all striving to improve consumer experience by rapidly testing hypotheses. This scenario begs the question: how effective can our threshold for identifying misleading results truly be while still fostering reasonable progress?

There sadly is no way out of this conundrum, except being rigorous and thoughtful. In domains which are critical such as health, it possibly involves developing an internal moral compass towards experiments, and not see their results as “wins” or “losses” as popularly painted, but merely as statistical artifacts.

Finally, I want to leave you with this this comic strip from xkcd, which is a poignant summary of my entire essay, in one picture. link